A website dedicated to animation, awards, and everything in between.

Credit: Autokar (Sylwia Szkiladz)

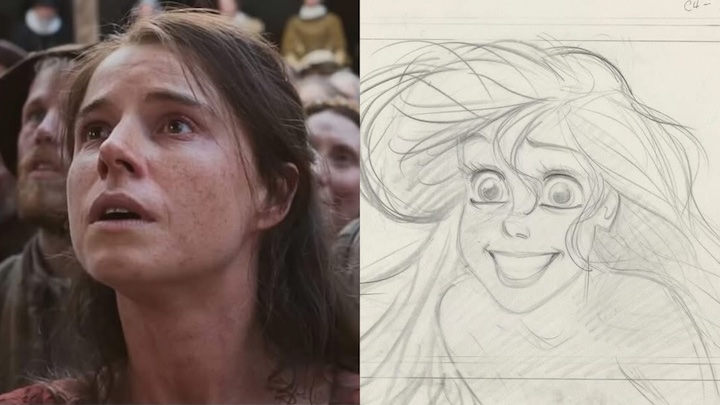

The animated short Autokar follows eight-year-old Agata, who retreats into her imagination and artistry as she travels from Poland to Belgium. Agata’s journey mirrors director Sylwia Szkiladz’s own childhood, having traveled from Podlaskie to Brussels at a young age. Autokar won the Golden Pegasus at the Animator International Animated Film Festival and the Gold Hugo at the Chicago International Film Festival, making it eligible for the 98th Academy Awards. Cartoon Contender spoke to Szkiladz about real-life inspirations, working with four studios, and telling a nostalgic immigration story that still resonates through a modern lens.

Credit: (Sylwia Szkiladz)

Q: Like the film’s main character, Agata, you’re originally from Poland and left to live in Belgium when you were eight. How much of your younger self is reflected in Agata?

A: There is a lot of myself in Agata. She is a character I created based, among other things, on my own emotions and memories. But within her, there are also many others, people who, like me, immigrated from Poland to Belgium in the 1990s. I spent time with them, and some have remained close friends. Agata and I share a curiosity about the stories of adults, as well as the courage to approach them, even if at first they might seem intimidating. Her journey is marked by the separation of her parents, which is also something I experienced in my own life. Her connection to nature, to animals, to her family, her home, and her native region near the Belarusian border is something I deeply relate to. The daydreaming that drives Agata to build an inner world, escaping into her imagination during long bus rides, is something I often did myself during my many journeys between Poland and Belgium, letting my imagination wander, blending the melancholy of departure with surreal associations.

Q: Just as the character escapes into her drawings, the film is like a living illustration from a children’s book. What were the artistic inspirations behind the film’s designs?

A: My first inspiration was a very strong, colorful sensation. I wanted the film to be felt as a colorful object in itself. Shades of gray reminded me of the communist period in Poland, with its abundance of concrete. The flashy colors made me think of the advertisements and clothing of the 1990s. I wanted the little girl, Agata, as well as the other characters, to stand out, radiant and more colorful, so as to give them importance and light. The bus is a character in its own right, with its pink curtains and seats patterned with cosmic motifs.

As for my inspirations and references, there are many illustrators I deeply admire. Tomi Ungerer for his bold line, Kitty Crowther for her use of fluorescent pink and empty space in "Petites histoires de nuits », Maurice Sendak for his embodied characters, Béatrice Alemagna for her textures, neon colors, and the attitudes of her child characters. The illustrated tales of my childhood, such as those by Jan Marcin Szancer and Marian Čapka, had a great influence on my imagination. Shaun Tan‘s graphic novel, The Arrival, also left a deep mark on me, with its blend of realism and magic.

In animation, Koji Yamamura for his settings and distortions in A Country Doctor; Anita Killi’s Angry Man for its exaggerations of size in relation to the child’s complex emotions and his letter to his father; Regina Pessoa and her wonderful film Uncle Thomas, in black and white with a flash of color that stands out and conveys such palpable emotion; Yuri Norstein‘s Tale of Tales and his use of light. The Moomins series by Tove Jansson, which I watched as a child, also inspired me. Each character is so particular, strange, endearing, embodied, and contrasted, it made me want to draw from reality to create fantastic characters.

Finally, Noémie Marsily, who worked with me on the sets, put a lot of herself into the visuals. She is an illustrator and director of fantastic animated films, and her contribution was crucial to the visual outcome of the film.

Q: Autokar was produced through four different studios: Ozù Productions, Novanima, Studio Amopix, and Vivi Film. What did each bring to the production?

A: Ozù Production are the main producers of the film, based in Brussels. They have an animation studio called L’Enclume, where I was able to work with the film’s team in a wonderful, welcoming environment. The studio is located in a former pasta factory that has been renovated, and the place is truly beautiful, it’s a great space to work in. We had our own little cocoon there, which was important for transmitting good energy into the film. The stages financed by Ozù included the layouts, part of the animation, and the backgrounds. They also financed the casting as well as the recording of the dialogues at Noiseroom Studio in Warsaw, with Polish actors and actresses. The music, composed by Barbara Drazkov, was recorded in Brussels. Finally, the film’s color grading was done at Charbon Studio in Brussels.

Vivi Film is the Belgian Flemish co-producer of the film. Their studios are not far from L‘Enclume. They financed most of the animation carried out in Brussels, as well as the coloring.

Amopix Studio, located in Strasbourg, France, financed the storyboard, the animatic, the editing, the animation, and the compositing. We were able to work on the animatic in their wonderful facilities right in the center of Strasbourg.

Novanima Studio, in Angoulême, handled script and animatic consultations during the dossier submissions. They took care of the sound effects at Le Bruit qui court studio, as well as the sound editing and the mixing of sound and music at Corto Studio. It was the first time I worked so extensively with a team at a distance. I was in Brussels while part of the animation team was in Strasbourg. I was worried that the distance might make the film feel less embodied, but in the end, it went very well. They did an excellent job.

Credit: Autokar (Sylwia Szkiladz)

Q: Agata encounters so many colorful characters on the bus. Were any of them based on real people you encountered growing up?

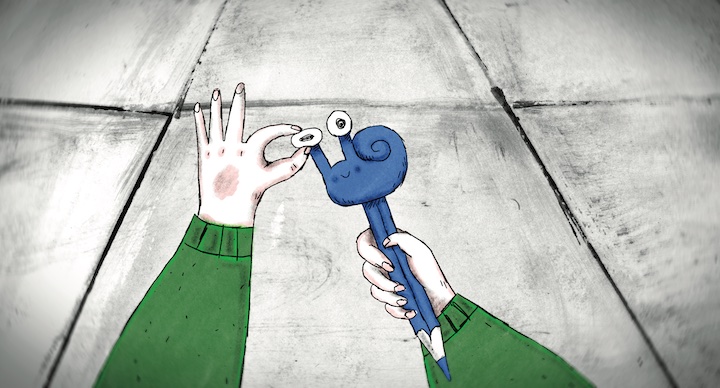

A: Yes, all of them were inspired by real people, by real encounters. It’s quite funny, I just had a screening in Poland at the Żubroffka Festival in Białystok (the city where Agata’s journey begins in the film). After the screening, a friend from that time, who also immigrated to Brussels, told me, “I think the owl lady looks like my mother.” What’s amusing is that when I was drawing that character, I was actually thinking of her mother. And she felt it! What I really wanted was to capture fragments of sensations and emotions. My idea was to work with archetypes, starting from real encounters I had as a child, which could represent different kinds of “losses” experienced by the bus characters. Each character loses something, or someone. And that is what they talk about. Agata, for her part, physically loses something in the bus: her pencil.

Q: I love how exaggerated elements of the film are. When Agata ventures under the bus seats, she literally shrinks down. When she hugs her grandparents goodbye, they practically pop like balloons. Is there a particular visual in the film that stands out the most to you?

A: The image that very clearly imposed itself on me was the one where Agata, very tall, pulls out her tiny house. The house, like an organ torn from the earth, still moves in her hands. The house is a little frightening yet moving, I wanted that scene to feel creepy-cute. It was a very important image, and I knew it had to be there. Another very clear image for me was that of the grandparents disappearing through the bus window as it drives away, at the end of the first sequence. They leave only a trace of themselves on the glass. I was helped by Augusto Zanovello with the storyboard, and he managed to translate that idea into an image.

Q: Autokar takes place in the 90s, but in what ways do you think its story of immigration applies to today’s world?

A: I believe that the emotions tied to immigration, the ones that come from within, are ultimately not so different from one person to another. Of course, every story is unique, but that feeling of loss, of loneliness, of everything going off track, becoming blurry, transforming, of sometimes being very small in the face of destiny, is something I think we all share when living through this experience. Naturally, some stories are more tragic than others. When someone leaves their country because of war, it must be far more complex. There is no certainty of ever finding one’s home again. But it is still a form of loss.

From the feedback I’ve received on the film, I feel that it resonates differently depending on each person’s journey. One viewer sees a reflection of their emotions linked to immigration, another sees a tale about the loss of a pencil, yet another finds a way to access the history of Poland in the 1990s,… My intention was to create a layered narrative, something that can be watched together, where each person finds something for themselves. A story that creates connection.

Credit: Autokar (Sylwia Szkiladz)

Q: How have Poland and Belgium shaped you as an artist?

A: Poland is the place of my childhood. I come from a village surrounded by forest, on the borders of the European Union. This region is full of human stories, often tragic, but also full of beauty tied to nature. Tales are part of everyday life, as people naturally share with one another the stories of their ancestors orally, creating connection. It’s something I deeply appreciate when I return. There are many human stories, traumas, emotions, and also a certain blur linked to history. And it is precisely within this blur that the imagination of the region lies, in my view, there is space for imagination. Many difficult stories from the past (war, deportations, etc.) are not told to children. But children sense them, they feel there is something more to know, to discover.

I believe this creates a fertile ground for investigation, for imagination. Personally, when I returned to Poland to visit my family, I would arrive with a list of questions that I unfolded once there to ask them. It surprised my grandmothers, but sometimes they answered, sometimes not. The energy contained in the lands of Podlasie inspires me because it is very particular. Polish is my mother tongue, the language I first learned to write in, the one that taught me how to leave a trace of a thought or a creation. And that is important for what came next.

In Belgium, what shaped me enormously was the access I had to different art schools and different environments. I began attending the academy on Wednesday afternoons at the age of 14, and I stopped going to Polish school instead. At first, I was shy about going, but my mother encouraged me. It became a place that liberated me. Later, I studied visual arts in secondary school at Saint Luc, and finally animation cinema at La Cambre. These art schools gave me access to encounters with people from artistic backgrounds, which was new for me. No one in my family worked as an artist. I was fortunate to have friends with whom I shared a lot, often spending several days in their families, and they came to mine. These “exchanges” within families were very beneficial in helping me build myself around different models, in different economic and socio-cultural environments. I think these exchanges truly impacted my desire to pursue this profession. They showed me that it was possible.

I would say that Poland gave me the fertile soil, and Belgium helped me plant and grow the seeds.

Q: Autokar has qualified for Oscar consideration by winning the Golden Pegasus at the Animator International Animated Film Festival and the Gold Hugo at the Chicago International Film Festival. What has it been like taking the film on the road?

A: Of course, it is an immense joy when a short film I worked on for four and a half years receives positive appreciation and finds its way to reach audiences. Many members of my family immigrated to Chicago for work during the communist era, including my grandmother and grandfather, who are represented at the beginning of the film. So the award at the Chicago festival carries a symbolic emotional weight for me and my family. Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to attend the festival, but I hope that one day I will be able to visit in person.

The premiere at the Animator Festival in Poznań was very important to me, it was the Polish premiere, and I attended with several members of the team. Barbara Drazkov, the composer of the film’s prepared piano score, was there, as well as Natalia Wolska, the young actress who plays Agata, Ewa Borysewicz, who was in charge of casting and consulted on the script and dialogues, and Michał Jankowski, who recorded the dialogues in Poland. Being together to present the film at the festival gave us that feeling of an extended family, which I love in this field, and which gives meaning to our work.

It feels incredibly beautiful that the film can touch different audiences in different countries. That is truly the power of cinema. The film is in Polish, and yet it managed to find its way to reach people in Chicago. And that is precious.

Credit: Autokar (Sylwia Szkiladz)

Q: Did you have a blue crayon/pencil with a snail eraser growing up?

A: When I was little, I had a lot of pencils, and I remember the very first trip my mother and I made in the 1990s to join my father, who had gone to work in Belgium. It was the very first time I was leaving home. I didn’t know where I was going, and I hovered around my mother, excited about this first journey, looking for something to do. My mother, busy, asked me, “Why don’t you prepare your pencils for the trip instead?”

I thought her idea was wonderful, and immediately began sharpening and arranging my pencils. I even remember cleaning them one by one so they would be perfectly neat when I arrived in Brussel. My pencils didn’t have little snail-shaped erasers, but they were still a refuge once I reached my destination. I drew much more than I had in Poland, because I didn’t speak French. Drawing became my way of communicating with other children, and it was magical.

Nick Spake is the Author of Bright & Shiny: A History of Animation at Award Shows Volumes 1 and 2. Available Now!