A website dedicated to animation, awards, and everything in between.

Credit: The Night Boots (Pierre-Luc Granjon)

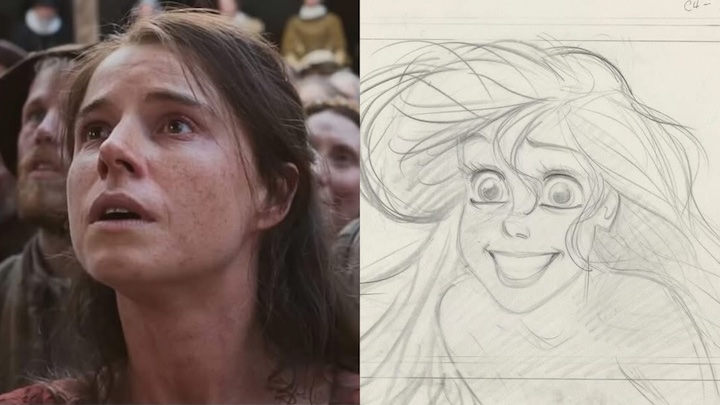

When young Eliot sneaks out into the forest one night, he finds himself engulfed in an environment that’s unsettling yet inviting. He discovers that appearances can be deceiving throughout The Night Boots, which won director Pierre-Luc Granjon the Cristal at Annecy for Best Short. This makes the film eligible for Best Animated Short consideration at the 98th Academy Awards. Granjon previously co-directed the 2023 feature The Inventor with Jim Capobianco. Cartoon Contender spoke with Granjon about his creative inspirations behind The Night Boots, the short’s pinscreen techniques, and winning Annecy with a “children’s film” that perhaps speaks more to adults.

Credit: Pierre-Luc Granjon

Q: Although the film has a shadowy, haunting aesthetic, we find that appearances can be deceiving. Was the film inspired by one of your own childhood experiences when you found that something wasn’t as scary as you thought?

A: I grew up in a house surrounded by fields and forest, and the forest was our favorite playground—mine, my brothers’, and my sister’s. Even in winter, when night fell early, the forest never seemed frightening to me; it felt familiar, and I was never afraid of running into the creatures that traditionally haunt such places in fairy tales, like witches, ogres, or big bad wolves. Instead, I felt as if I myself belonged there. In my films, I play with this cliché of the scary fairy-tale forest, letting the viewer believe that danger is lurking when, in fact, it isn’t.

Q: The designs strike a balance between creepy, cozy, and charming. What were your influences behind the film’s visuals?

A: I like it when the characters in the films I watch aren’t too polished, when they keep a sense of mystery. And in the same way, it seems important to me that the places where these characters evolve have depth—that they’re not there just to “look pretty,” but to reinforce the film’s intent. They shouldn’t be mere backdrops.

When I write a new project, I try to forget all the people I admire so as not to fall under their influence, but their films and books have nourished my imagination, and I can’t completely set them aside. I’m thinking, for example, of Yuri Norstein and Hedgehog in the Fog. It’s a film that one might find a bit sad or unsettling, with its muted colors and autumnal atmosphere. But it’s a warm film, full of life! I could also mention Palmipédarium by Jérémy Clapin, which captivated me with its message, its design, and its atmosphere. Or Jean-Luc Gréco and Catherine Buffat, so original and unlike anyone else. I’m also very fond of the work of Tove Jansson (the Moomins), who creates wonderfully surprising characters and combines a certain darkness with delightful adventures. I’ll stop here, but the list is long.

Q: The Night Boots was brought to life using pinscreen animation. Can you take us through how this technique works and what drew you to it?

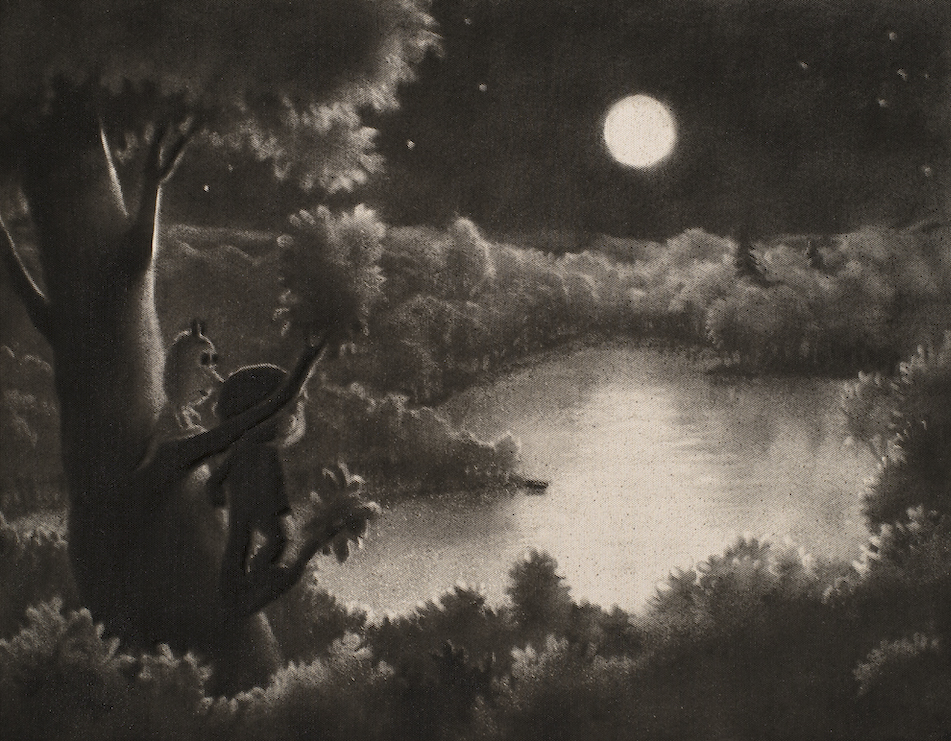

A: I used an Alexeieff/Parker pinscreen called L’Épinette. It is a metal frame filled with 277,000 white tubes. Inside each tube is a pin that extends 5 mm beyond the tube. When all the pins are pushed in, you see only the cut ends of the tubes, and the screen appears white. When the pins are pulled out, they cast shadows on the surface (we use only one projector to light the pinscreen), and these shadows create different shades of grey and black.

I decided to use the pinscreen because I felt it was the right tool for my project, which takes place on a full-moon night in the countryside. When I draw on a pinscreen, I feel as though I’m sculpting light and shadow—chiaroscuro. When all the pins are out, the screen becomes black, almost like black velvet. To push the pins in, I use small glass tools (a pointed bulb works well), and I draw with them like I would do with a pen, and suddenly light appears. It’s a kind of magic!

Q: The whole film has an almost storybook-like quality to it, the kind you’d read before going to bed. Were there any picture books from your childhood that shaped you as an artist?

A: As a child, I read a lot of comic books, especially those by Peyo. I would immerse myself completely in these adventures, and I remember that sometimes, in my dreams, I was part of those worlds. We were also subscribed to a magazine called "J’aime lire," and our parents would read us the many stories, some of which took me far away. At 14, I read The Lord of the Rings, and I was completely blown away. The idea that an author could create an entire universe, an entire world, by his own was extraordinary. Later, I discovered Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak. Absolutely amazing!

Credit: The Night Boots (Pierre-Luc Granjon)

Q: The Night Boots is your first directorial outing since the feature The Inventor, which you made with Jim Capobianco. Having tackled both, do you prefer working in features or shorts?

A: My preference probably leans toward short films, as they are lighter projects, easier to finance, and, it seems to me, they allow for greater creative freedom—no doubt because they involve fewer financial partners who might otherwise have a say in the script, the visual style, the editing, and so on. But experiencing a feature film is something everyone should go through! A whole team is involved, and above all, the adventure is a collective one. And if you manage to maintain a good atmosphere despite the pressure of deadlines, they become wonderful and joyful moments. Not to mention the pleasure of being able to develop a story and follow characters over a long narrative.

Q: I find that a lot of directors don’t know how to light scenes set at night. This isn’t the case in The Night Boots, where I can always make out what’s going on. What do you think is the key to depicting the night?

A: First of all, thank you very much! But above all, I must thank the pin screen, which makes it possible to work with lighting in a very subtle way. It was especially enjoyable to work with backlighting, for example. I also allowed myself quite a bit of freedom throughout the film. Once I had made the audience understand that the story takes place on a full-moon night, there was no need to constantly remind them of it. When the characters’ emotional experience took precedence over their surroundings, I chose to fade out the setting entirely, leaving only a grey or white background. This also helped prevent the film from becoming overly dark.

To depict the night, sound also plays a crucial role, and together with Loïc Burkhardt, the sound editor, we sought to make this night as rich and deep as possible. There is a whole crowd of insects, furred and feathered animals, creaking sounds, and leaves in the wind — all of this adds to the image so that the night can truly exist.

Q: Black and white perfectly fits the film’s ambiance, but did producing it in color ever cross your mind?

A: In its most classical use, the pin screen requires working in black and white, since the image is created through the shadows cast by the pins. However, at the NFB, Jacques Drouin and Michèle Lemieux managed to introduce color into the pin screen, mainly through the use of colored light sources. The effect is entirely convincing. For Les Bottes de la Nuit, since it was my first film truly produced on a pin screen, I wanted to use it in its most traditional form, with a single light illuminating the screen and a fixed frame. And the fact that the story takes place at night justified this choice, as all colors then lose their saturation.

I have often presented my film to children, and at very different moments I was asked three questions that I found especially delightful: “How did you make the straw yellow?”, “How did you make the headlights yellow?”, and “How did you make the lake blue?” I would answer by talking about the influence of sound on the way we perceive images. But this also answers your question: even in black and white, it is possible to color a film’s atmosphere, to make it feel cold or warm — and for Les Bottes de la Nuit, that was more than enough.

Q: The Night Boots won the Cristal at Annecy for Best Short, qualifying it for the Oscars consideration. Can you take us through that experience, as well as any other festival highlights?

A: I have been a filmmaker for over 20 years, and this is the first time one of my films has met with such success. Most of the time, my films feature children as their protagonists, and as a result, they are often considered to be children’s films. But I sincerely try to address everyone, in the hope that adults will rediscover a part of their own childhood. I had always told myself that this “children’s film” label would prevent me from ever receiving an award such as the Cristal at the Annecy Festival, and I am all the happier to have been proven wrong! It was an extraordinary moment, following the Audience Award and the André Martin Award. We may tell ourselves that we don’t make films for prizes, but receiving one is always encouraging and deeply gratifying! My producer, Yves Bouveret, and I were on cloud nine — and truthfully, we still are, as the adventure of Les Bottes de la Nuit does not yet seem to be over!

Nick Spake is the Author of Bright & Shiny: A History of Animation at Award Shows Volumes 1 and 2. Available Now!