A website dedicated to animation, awards, and everything in between.

Credit: Winter in March (Natalia Mirzoyan)

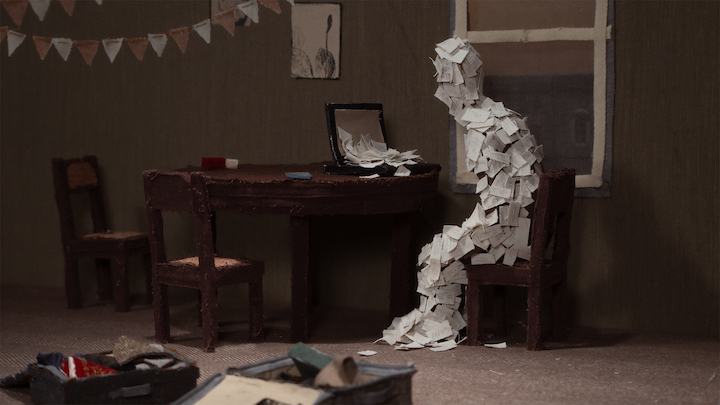

Using stop-motion puppets, Winter in March tells the true story of Kirill and Dasha, a Russian couple who fled from St. Petersburg amid the invasion of Ukraine. Director Natalia Mirzoyan (Mirzoian) previously made the animated shorts My Childhood Mystery Tree, Chinti, Five Minutes to Sea, and Merry Grandmas. For Winter in March, she won the Heart of Sarajevo for the Best Short Film at the Sarajevo Film Festival. This qualified the film for consideration at the 98th Academy Awards. Cartoon Contender spoke with Mirzoyan about the Russo-Ukrainian war, the real people who inspired her film, and the care embroidered into every frame.

Credit: Winter in March (Natalia Mirzoyan)

Q: How did you first meet Kirill and Dasha?

A: I knew them years before. We worked with Kirill at the same studio. He is [an] animator as well. And Dasha is [a] children[’s] theatre director.

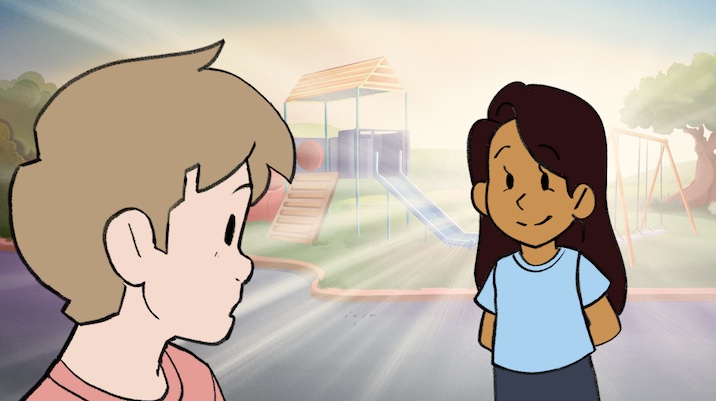

Q: While this isn’t your first animated short, it is your first time working with puppets. What inspired you to tell Kirill and Dasha’s story with these distinctly designed dolls?

A: I [came] to study puppet animation in Estonia. So, it was initially my desire to make a puppet film. But concerning this story, it was not [an] obvious decision because it’s a road movie with many characters and sets. So that is why something is flat - we just didn’t have time and budget. But I like[d] this eventually.

Q: I love how it isn’t just the characters who look like they were stitched from scratch. The whole world is comprised of fabric. Even the water appears to be stringy while the snow looks like cotton. To me, it’s a fitting metaphor for a world coming undone as people unravel. Was that the intent?

A: Once I made [a] decision about textile and embroidery, it helped me a lot to express the story, to show through visual metaphors what [the] characters [were] feeling and experiencing. Textile is something which protects body, but [on] the other hand, it is very fragile. It can be easily torn. I feel the same about nowadays world around me.

Q: Along with Kirill and Dasha, you interviewed a few different people about their experiences regarding war and immigration. Were there any other stories that stood out to you?

A: It was more about feelings. And the story is also my story, as my family immigrated from Russia in 2022. Kirill and Dasha[’s] story seemed to me very universal, but also their journey was filled with many details which seemed to me very cinematographic. Some images impressed me - like soldiers with snow on their helmets. Actually, the film started from this image.

Credit: Winter in March (Natalia Mirzoyan)

Q: In addition to traditional stop-motion techniques, Winter in March uses embroidery animation. It reminded me a bit of Yegane Moghaddam’s Oscar-nominated short Our Uniform. Was that at all an inspiration?

A: I saw the film of Yegane later, after I started the film. But eventually she supported me and my film a lot. So, we remotely became friends. I think that she had painting on the textile, not embroidery. But I was very much inspired by Sweden artist Britta Marakatt-Labba and Russian artist Alisa Gorshenina - they both work with textile and hard topics.

Q: Speaking of the Oscars, Winter in March has qualified for consideration by winning the Heart of Sarajevo for the Best Short Film at the Sarajevo Film Festival. What has it been like taking the film on the road to festivals?

A: The festival journey began very spontaneously. We submitted the unfinished film to Cannes without having distribution, and when it was selected, we had just two months to complete it. After that, I didn’t send the film anywhere for a while — I’m actually handling the distribution myself now. The festival circuit picked up again in August, and Sarajevo was the second festival for the film. It’s mainly a film festival, and mine was the only animated film in competition. Because it happened so early, I had considered waiting to go for the Oscars next year, but we decided not to — our world feels so fragile right now, especially with the situation in Estonia. And now the film has started [a] very intense festival life.

Q: In the closing text, it’s mentioned that Dasha moved on and settled in Serbia while Kirill chose to stay in Georgia. Have you been in contact with either of them since the film came out?

A: I am in contact with Dasha. She tried to come to Cannes but couldn’t get [a] visa, but later she managed to visit Sarajevo [Film] Festival.

Credit: Winter in March (Natalia Mirzoyan)

Q: It’s also mentioned that by the time you finished the film, the Russian invasion of Ukraine had lasted for three years and was still ongoing. When you started production, did you ever imagine that this conflict would last well beyond the film’s completion?

A: To be honest - never. I was sure that the war will be far in the past and it will be more appropriate to speak about my topic. But unfortunately, it got only worse. More wars. More dictatorship. Surprisingly, this film became relevant not only for Russian people. Actually, helplessness to stop the wars became [a] very universal feeling. It makes me sad, but I hope that at least [I] can share this feeling with other people with this film.

Nick Spake is the Author of Bright & Shiny: A History of Animation at Award Shows Volumes 1 and 2. Available Now!